What will happen to local producers if FG opens borders for cement importation?

![The top three players in the Nigerian cement market. [ICIR]](https://image.api.sportal365.com/process/smp-images-production/pulse.ng/27072024/eb38b4bd-66f8-4406-bcec-c517af69a2b6?operations=autocrop(700:467))

The recent hike in the price of cement has prompted the Federal Government to consider opening the borders to allow the importation of cement and prevent a recurrence of ‘unreasonable’ price hikes by local manufacturers.

In January 2024, a 50-kilogram bag of cement sold for ₦6,000 but in February, the price surged astronomically to between ₦10,000 and ₦15,000.

Unsettled by the development, the FG convened a meeting with cement manufacturers and pleaded with them to bring down the prices of the product.

During the meeting, the major manufacturers — Dangote, Lafarge and BUA — agreed to sell a 50kg bag of cement at a retail price of between ₦7,000 and ₦8,000, provided the FG fixes the challenges of gas shortage, import duty, and road network.

Depending on the location, a bag of Dangote cement in the Oshodi-Isolo area of Lagos State currently sells at ₦11,500.

Interestingly, 24 hours after the initial meeting, the FG, represented by Ahmed Dangiwa, the Minister of Housing and Urban Development, in an emergency meeting with cement and building materials manufacturers, threatened to open borders for cement importation if the local manufacturers failed to bring down their prices.

The FG’s argument

The government believes the recent increase in the price of cement was not justified because the limestone, clay, silica sand, and gypsum used in manufacturing the product are locally sourced.

![Cement manufacturers during their meeting with the Federal Government represented by the Minister of Works, David Umahi. [Media Bypass]](https://image.api.sportal365.com/process/smp-images-production/pulse.ng/27072024/211ff338-8994-431b-9de3-b2303396c2cf)

Dangiwa argued that the production of cement should also not be affected by the forex crisis crippling the Nigerian economy.

He maintained that the gas, which the manufacturers mentioned as one of the conditions for reducing cement prices should also not be factored into pricing because it is locally produced.

“The gas price you spoke of, we know that we produce gas in the country. The only thing you can say is that maybe it is not enough. Even if you say about 50% of your production cost is spent on gas prices, we still produce gas in Nigeria. It's just that some of the manufacturers take advantage of the situation,” the minister said.

Dangiwa also faulted the claim by the manufacturers on how their mining equipment contributes to the high prices of cement, saying they bought the equipment a long time ago at a lower price.

He believes using the current exchange rate for the price of the equipment is a mischievous excuse to increase the price of cement.

These formed the basis of the minister’s threat that the FG would resume importation of the product if the manufacturers refused to play ball with the government.

Why did FG ban cement importation in the first place?

The history of cement manufacturing in Nigeria dates back to 1957 when NIGERCEM was established as the first indigenous cement plant in Nkalagu in present-day Ebonyi State.

![NIGERCEM factory is located in Ebonyi State. [Maazi Ogbonnaya Okoro/X]](https://image.api.sportal365.com/process/smp-images-production/pulse.ng/27072024/f8cc8f7e-6b63-4530-8445-589422ae4013)

Three years later, another cement plant, the West African Portland Cement Company was established in 1960, in Ewekoro, Ogun State.

In 1980, the FG floated the Benue Cement Company Plc at Gboko in Benue State.

However, by 1999, two of the three factories had gone under and with increasing demand for cement, Nigeria switched to the importation of bagged cement.

This subsisted until 2002 when former president, Olusegun Obasanjo, initiated a backward integration policy as import substitution for the cement industry.

The idea was to encourage cement importers to establish manufacturing plants to satisfy local demands.

In his assessment of the cement industry, Obasanjo felt it was unacceptable for Nigeria to import cement given the large deposit of limestone in various parts of the country.

With Obasanjo’s policy creating an enabling environment for investors and industry players to float factories, Dangote Group established its first and largest cement factory in Africa in Kogi State as well as two other plants in Ibese in Ogun, and Gboko in Benue.

The policy also paved the way for other industry players like BUA to establish cement plants in Sokoto and Edo.

Sadly, by the end of Obasanjo’s government, it had become clear that the local manufacturers could not satisfy the local demands.

This prompted his successor, the late former president, Umar Musa Yar’Adua, to reverse the ban in 2007 and give licenses to more importers of cement to stabilise the rising price of the product.

Fast-forward to 2015, in a bid to encourage local production, the immediate former president, Muhammadu Buhari, banned the importation of cement alongside 40 other items.

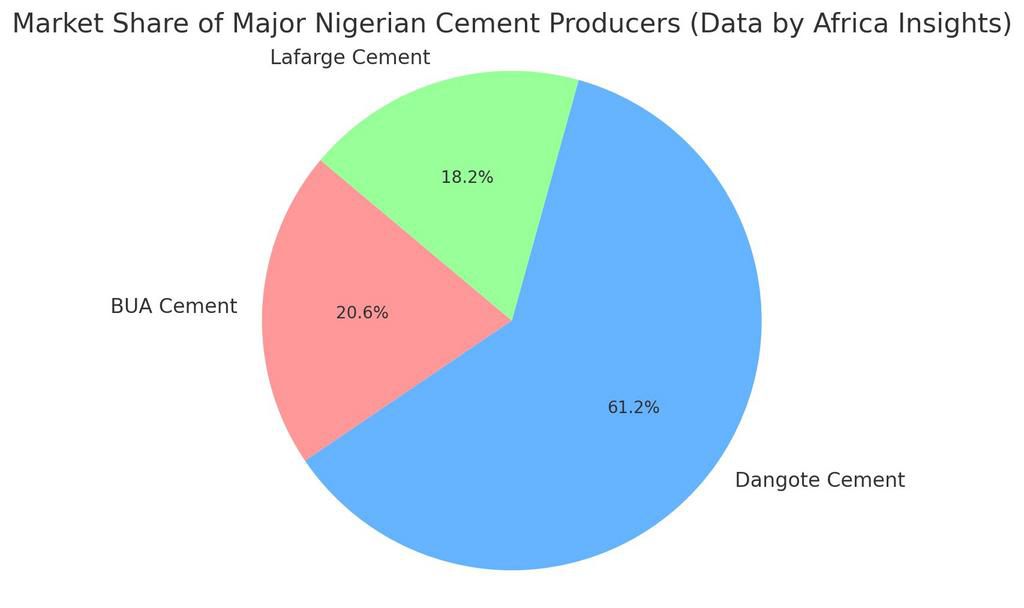

This left Nigeria with Dangote Group, Lafarge Africa and BUA Group as the three major cement manufacturers in the country.

So, what does importation portend for manufacturers?

The Federal Government considered the opening of borders for cement importation because it believes cement producers are making excessive profits at the expense of Nigerians.

Despite Nigeria being home to three of the largest cement producers in Africa, the price of the product is adjudged to be too expensive for a country that is blessed with limestone and other resources needed for cement production.

![Dangote Cement plant in Obajana, Kogi State [Daily Trust]](https://image.api.sportal365.com/process/smp-images-production/pulse.ng/27072024/8af11d3d-ffaa-4c6a-a038-e8d7a1f1def1)

While the government’s view is not completely invalid, it is important to note that the Nigerian cement industry is marked by consistent demands culminating in significant supply gaps. This explains the incessant increase in the price of the product.

So, if the government’s plan to address the high price is to open its borders for the importation of the product, the outcome would certainly affect local manufacturers in many ways depending on the scale of importation and the price of the imported product.

Ostensibly, the government’s threat to open borders was meant to prompt local producers to reduce the prices of their cement, as the importation of cement would create price competition between them and licensed importers.

With more options available in the market, the supply gap would shrink but local manufacturers would lose some of their market shares to the importers.

Also, if the imported cement is offered at a lower price and Nigerians — given their obsession with anything foreign — consider it to be of better quality, the local manufacturers would be forced to beat down their prices.

However, if the FG allows cement importation and the move fails to satisfy local demands, Nigerians will bear the brunt because the forces of demand and supply and the greed of manufacturers would keep the price unreasonably high.

)

![Aisha blows hot on Security forces; Y7ou won't believe what she said [VIDEO]](https://image.api.sportal365.com/process/smp-images-production/pulse.ng/17082024/1f976edf-1ee2-4644-8ba1-7b52359e1a8f?operations=autocrop(640:427))

)

)

)

![Lagos state Governor, Babajide Sanwo-Olu visited the Infectious Disease Hospital in Yaba where the Coronavirus index patient is being managed. [Twitter/@jidesanwoolu]](https://image.api.sportal365.com/process/smp-images-production/pulse.ng/16082024/377b73a6-190e-4c77-b687-ca4cb1ee7489?operations=autocrop(236:157))

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)