What it means to be trapped awaiting trial in Nigeria's prison system

)

Around midnight, in the early hours of April 29, 2015, Rasheed Adetunji, a 27-year-old disc jockey, was playing at a birthday party at Eleko Beach in the Lekki area of Lagos State.

He'd played many such parties at the beach for a few years, but that night was different.

Around 1 am, his frantic-looking landlord made a surprising appearance at the party and led him outside where his pregnant wife and mother-in-law waited. Police officers were there too, and had seized his neighbours' phones, assembled in a bowl, so no one could tip him off.

The officers had searched his home and then searched his car — which he sometimes used for commercial cab driving — looking for evidence to confirm their suspicion that he was part of a kidnapping gang. He started crying.

"It's a bad memory for me," Adetunji recounted nine years later to Pulse Nigeria. "The day I entered custody, I was half-dead."

How Adetunji landed in prison

Adetunji was raised by his blind father in Ibadan before he moved to Lagos to find his way, but nothing prepared him for his encounter with the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS), a now-defunct police unit notorious for extra-judicial acts.

SARS officers tortured him on his first night in detention and demanded a confession of guilt. He refused and was so badly beaten he could not eat for three days which he spent in pain on the cell floor nursing a horrible leg injury.

His injury was only patched with a bandage to make him presentable for a media parade.

"The investigating police officer (IPO) said if I said anything contradictory to what they told me to say, they'd kill me," Adetunji told Pulse. "What I told the media that day was under threat of death. I can't even remember."

After two months in SARS custody, he appeared before a court in June 2015 alongside two other people he'd never met. They were immediately remanded in Kirikiri Maximum Prison. He would never see a courtroom again for six years.

Adetunji's prison experience didn't get off to a great start. His fragile condition made it impossible to accommodate him in an overcrowded cell where the sweat of one man in a side-way sleeping position rubbed on the next man's sweat. He spent a week at the hospital recovering from all the unpleasantness of his SARS stay.

His family got him a lawyer, but he didn't stick around for more than three months. They barely had enough to hire another lawyer and months became years for the inmate who had no idea what was happening with his case.

He haunted the Records office at the prison, but the troubling feedback he kept getting was the court could not locate his case file. Technically, he didn't exist in the system that put him in prison. "I was at a stage of telling the warder to take me to court to tell them I'm guilty so they could sentence me to death," he said.

When Adetunji met Oluyemi Orija through his prison pastor in 2019, the lawyer had just set up Headfort Foundation, a non-profit organisation that provides free legal services for poor people stuck in prison with no legal representation.

It took over a year before the issue of his non-existent case file was resolved and a second court appearance was finally set for March 2020. It was the last month before the country went into a COVID-enforced lockdown, and the courts shut down.

"Immediately you hear your name to go to court, especially most of us who have been abandoned in that place, the excitement is like you're going home that day," he noted, highlighting the disappointment of the lockdown's disruption.

But the interruption didn't last forever and he finally saw a courtroom again in July 2021 only to suffer a series of adjournments marked by the prosecution's failure to present a coherent case or witnesses.

After numerous adjournments with the case heading nowhere, the judge finally told him on February 1, 2023 he was free to go. Adetunji had nowhere to sleep that day so he had to return to spend one last draining night inside the prison. On February 2, 2023, almost eight years after his arrest, he was finally a free man.

Awaiting trial behind bars

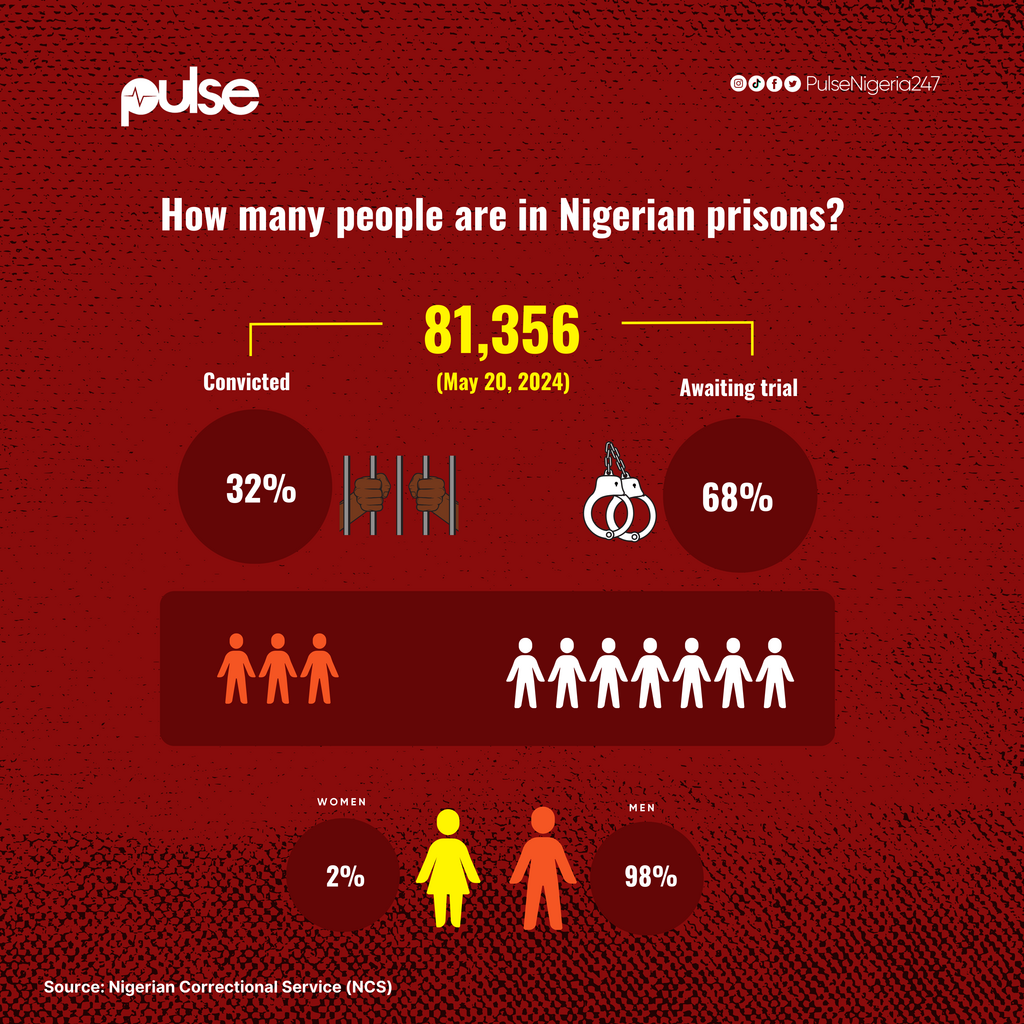

Adetunji's case is only one of many in the Nigerian justice system. According to public records compiled by the Nigerian Correctional Service (NCS) as of May 20, 2024, 68% of inmates in prisons are awaiting trial. Many factors are responsible for this.

Orija thinks one of the most critical factors is corruption at every stage of Nigeria's criminal justice system — police stations, courts, and prisons, or correctional centres as the government likes to call them these days.

"If you have 500 cases in court today, I can guarantee you that about 300 of them will be thrown out by the court and that's because the police are not doing any form of investigations, they're just making arrests to make money. Nigerians have now gotten to that stage where we exchange money for our freedom," she told Pulse Nigeria.

The courts are overwhelmed by the burden of unnecessary cases cooked by the police, and this causes further delays in the administration of justice, according to the lawyer.

She noted that unprepared lawyers also contribute their quota of problems, seeking adjournments that cause a case that should typically be settled in a year to stretch to five.

Judges are complicit in their unique ways, Orija said, setting tough bail conditions that are unachievable for poor people, with the unintended consequence of making their situation worse, especially for petty offences, like indebtedness, that are legally not criminal cases.

The government isn't a stranger to the problem of awaiting-trial inmates, but lip service has been paid to sustainable solutions to ease the unnecessary suffering of thousands of citizens.

The correctional centres are where the mass of inmates' horrible experiences happen, but the spokesperson of the Lagos Command of the NCS, Rotimi Oladokun, believes the Police Force and other arresting agencies are where the focus should be.

"For prosecuting agencies, the basic thing is to investigate. When you have your facts, arrest, go to court and prosecute. But when you don't have facts and think the court should remand someone before you start looking for evidence, there's a problem," he told Pulse.

According to Oladokun, the NCS provides a platform for inmates to have access to education, vocational training and other helpful programmes, as well as a review mechanism to ensure awaiting-trial inmates aren't in there forever. But this is never enough.

Ikemesit Effiong, partner and head of research at SBM Intelligence, believes the problem persists because Nigeria's justice system is set up to be clumsy.

"Operationally, the entire prosecutorial ecosystem is not designed with a mind towards speedily resolving cases, very little proper investigation happens," he noted.

Pulse Nigeria spoke to other former awaiting trial inmates like Segun Esan, who spent six years in prison after police officers seized his motorcycle; Jonah Daniel, who spent an extra four years in prison even though the court had released him; and Olanrewaju Oladejo, who spent eight years in prison after a mob wrongly accused him of theft.

Orija has an obvious stopgap solution for anyone who falls into the trap of Nigeria's ill-equipped justice system. "The Nigerian justice system is complicated to navigate, even for lawyers. If you get caught in this system and you're not informed, get a lawyer," she offered.

It's one solution that fixes a specific portion of the problem. Ikemesit wants to see a complete overhaul of a system that's clearly not working efficiently enough. "All of the various moving parts of the criminal justice ecosystem — police, prosecution, the bench, as well as our lawmakers — should create the framework to incentivise a speedy resolution of cases," he said.

"You can't have a society argue that you have respect for the sanctity of life if you can unduly imprison people for decades and decades and we're all comfortable with it," the analyst added.

ALSO READ:

![Aisha blows hot on Security forces; Y7ou won't believe what she said [VIDEO]](https://image.api.sportal365.com/process/smp-images-production/pulse.ng/17082024/1f976edf-1ee2-4644-8ba1-7b52359e1a8f?operations=autocrop(640:427))

)

)

)

![Lagos state Governor, Babajide Sanwo-Olu visited the Infectious Disease Hospital in Yaba where the Coronavirus index patient is being managed. [Twitter/@jidesanwoolu]](https://image.api.sportal365.com/process/smp-images-production/pulse.ng/16082024/377b73a6-190e-4c77-b687-ca4cb1ee7489?operations=autocrop(236:157))

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)