Addressing dyslexia in Nigeria: From koboko approach to evidence-based learning

)

In Abuja, Nigeria, Dyslexia Help Africa (DHA) is driving an educational initiative that focuses on comprehensive reading intervention and support for children with dyslexia.

This programme combines advocacy, educator training, and a specialised learning intervention platform.

Through patient guidance and innovative teaching methods, this initiative is breaking down educational inclusion barriers for kids with learning disabilities by promoting evidence-based strategies and empowering dyslexic learners.

DHA is creating a more inclusive environment for both neuro-diverse (kids whose brain processes, learns, and/or behaves differently) and neuro-typical kids (referring to someone who has the brain functions, behaviors, and processing considered standard or typical).

"Koboko," a local name for cane in Nigeria, seems to be how many parents with no knowledge of this condition, respond, having misdiagnosed their child's learning disability as stubborness.

"For kids with dyslexia, the first solution is not the cane, it is to understand that there is a brain condition that needs your help, patience and assistance," says Blessing Ingyape, a dyslexia coach.

Breaking down barriers

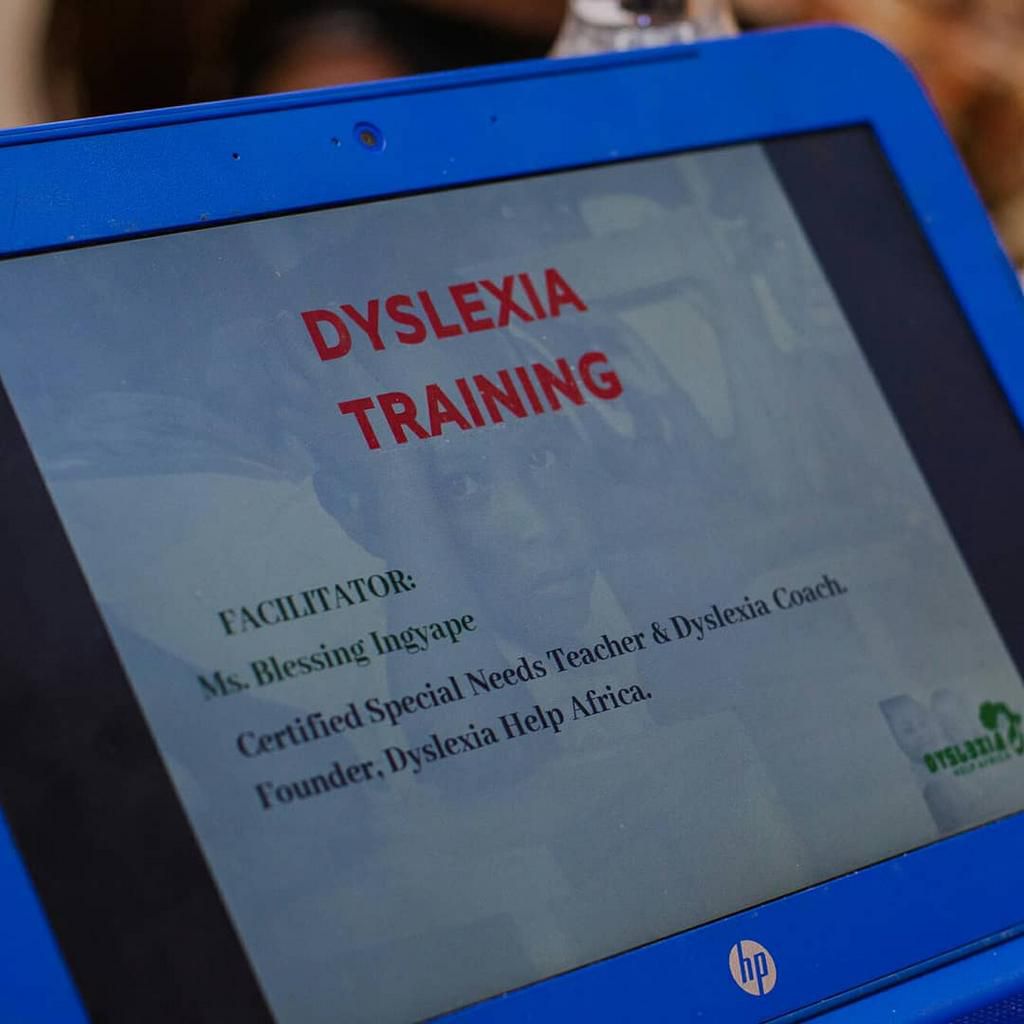

Ingyape, an international certified special needs educator, is the founder of DHA, and programme director at Dyslexia Help Online Learning Academy.

The coach and her 10 children have been going back and forth with phonemic mastery for a couple of weeks now and she is hell-bent on making sure they conquer all the challenges a dyslexic child encounters learning to read and write.

"Say toothbrush without tooth."

"Say doughnut without dough."

Many times in the initial stages of these learning interventions, the silence from the students can be deafening. They want to pronounce these words or read them properly but you cannot begin to imagine the battle that goes on inside the brain of a dyslexic as they struggle to articulate, words, spelling, sound and speech.

A typical class day would be her asking questions like, "How do you pronounce 'cup' without the 'c' sound?" Then you would hear a kid say "brown", an entirely unrelated answer to the question asked. Ingyape would be on it until the child finally gets it. This patience and deliberateness has brought her the kind of results she's had with many dyslexics.

"What makes the difference for me is that I ensure the child has gotten it. It is not about if I have taught it, the question should be, 'Has the child gotten it?'

"If you need to move on, you need to find other creative and fun ways to ensure the child gets it before moving on."

This is what learning to read looks like for the 100 kids who have gone through the academy.

Recognising the need

Dyslexia Help Africa emerged in response to the growing awareness among parents and teachers that some children's reading and learning struggles might be attributed to dyslexia or other learning disabilities.

According to United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), the prevalence of dyslexia is high, with estimates suggesting that 10% to 20% of the global population is affected by this learning disability. In low-income communities, the percentage could even reach 30%.

Lola Aneke, a renowned neurodiversity evangelist and dyslexia coach, asserts, "At least one dyslexic child can be found in every classroom."

In Nigeria, where DHA operates, approximately 20% of the population is dyslexic, and a significant portion of that consists of schoolchildren labelled with "specific learning disabilities." However, awareness and understanding of dyslexia remain relatively low in the country.

Understanding neurodiversity

According to Ingyape, "The Learning Academy serves as an intervention centre rather than a traditional school. The kids come in, and we help put them back on their feet. We have kids who do after-school classes, others take a term out of school, just to come and learn how to read and then go back."

It's common for kids with dyslexia to also have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) — you may hear this called comorbidity. This comorbidity of ADHD and reading disorder (RD) is frequent. The International Dyslexia Association estimates that at least 30% of individuals with dyslexia also have ADHD, highlighting the importance of addressing both conditions comprehensively.

The passion to make a difference

Ingyape, inspired by her own experience witnessing classmates drop out of school due to learning difficulties, pursued training and certification in addressing neurodiverse children's needs.

Armed with a certification that covered 13 learning disabilities and knowledge of effective strategies, she decided to focus on dyslexia, leading to the establishment of the initiative.

Before DHA, Ingyape provided classroom support to dyslexic children in various schools, observing their struggles firsthand and recognising the need for targeted interventions.

"At Dyslexia Learning Academy, we currently have a 12-year-old who has authored a book. When she came into the academy, she could neither read nor write. This is because, at the beginning, we discovered her love for poems and started teaching along her strengths and towards her passion. So now she's a 12-year-old dyslexic who is confident and has already begun working on her second book."

Making a difference

The academy, which started in 2022, three years after DHA's inception, initially served as an advocacy platform to raise awareness about dyslexia.

Most people don't even know that their kids are struggling so they can look for help, others were in denial but the truth was starring them in the face, every classroom had at least one child who was struggling with reading and learning.

Eventually, parents and teachers began reaching out for assistance. Using a structured literacy program, the academy takes a step-by-step approach, ensuring mastery of each goal before moving forward.

"We don't put the responsibility on the children, we put the responsibility on us. So if the child is not getting it, it is not the child's fault," said Ms Pat who works as a dyslexia coach at the academy.

The screening process involves observation, looking for red flags like, difficulties with reading, spelling, and pronouncing words, as well as challenges in processing and retaining information, followed by the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (CTOPP) assessment to diagnose and understand specific challenges.

The CTOPP just checks the phonological processing of the child when it comes to blending words and phonemic awareness. "First, we try to see how well a child can understand the phonemes they're hearing," Ingyape said.

When teaching about dyslexia and reading, there are three key areas of the brain to focus on — auditory processing, visual processing, and memory.

Auditory processing refers to the child's ability to process and distinguish different sounds in words. Dyslexic individuals may struggle with this skill.

Visual processing involves the ability to quickly recognise and comprehend words without having to decode them letter by letter.

Sight words play a crucial role in this process, as dyslexic learners need to develop fluency in recognising common words. Memory, both short-term and long-term, is essential for retaining and recalling information.

"By targeting these areas of the brain through drills, our intervention aims to strengthen the underdeveloped regions associated with dyslexia and support reading and spelling skills," Ms. Pat said.

Expanding impact through volunteerism

Through their literacy project, DHA helps kids in low income areas and IDP camps. They provide complimentary screenings and reading interventions to children with difficulty.

To extend its impact, the initiative trains volunteers who commit six months of their time to work with dyslexic children. Currently, eight volunteers across three states (Abuja, Lagos and Ogun) have worked with a total of 75 children and counting, continuing DHA's mission voluntarily.

Parents and guardians of children who have benefited from DHA's intervention express gratitude for the positive impact on their children's lives. From improving self-confidence to enhancing literacy skills, the initiative has brought joy and hope to these families.

"My son was over five when I came across the Dyslexia Help Learning Academy. At that time, he didn't even know his alphabet, I felt helpless. I didn’t know where to start until I discovered Dyslexia Help.

"Today, big words no longer scare him. The day he picked up a book and read the word 'character,' his dad was shocked," Annie Igwe said, adding that her son is seven now and can read sentences and more complex words.

"Thank you, Dyslexia help Africa," she said with Joy.

For Chinwe Attama, "The intervention of Dyslexia Help Africa brought so much joy to her family. My daughter, Oloaku, gained so much self-confidence, and she is eager to see and learn new words.

"There are signs and indications that she will keep improving her learning and behavioural attitude," she said, thankful to the organisation for the impact.

Despite a shortage of trained hands and limited support from schools and parents, Ingyape said she is proud of her decision to start and run the academy as she has been able to help many kids.

Dyslexia Help Africa's commitment to transforming learning for neurodiverse and neurotypical children in Abuja, Nigeria, and beyond is commendable.

By providing comprehensive reading intervention and support, advocating for awareness, and empowering educators and parents, DHA is fostering a more inclusive and equitable educational environment.

Through their efforts, they are not only changing the lives of dyslexic children but also improving literacy skills in vulnerable populations.

With a passionate team and a dedicated vision, Dyslexia Help Africa continues to make a profound impact on the lives of children struggling with dyslexia, unlocking their full potential in the educational sector.

***

Tzar Oluigbo is a passionate storyteller, investigative journalist, and advocate for social impact in Africa. With a relentless pursuit of truth and a heart for positive change and positive narratives to social problems. Tzar weaves compelling narratives that shine a light on solutions and inspire transformation.

***

This story was produced with the support of Nigeria Health Watch through the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organisation dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

![Aisha blows hot on Security forces; Y7ou won't believe what she said [VIDEO]](https://image.api.sportal365.com/process/smp-images-production/pulse.ng/17082024/1f976edf-1ee2-4644-8ba1-7b52359e1a8f?operations=autocrop(640:427))

)

)

)

![Lagos state Governor, Babajide Sanwo-Olu visited the Infectious Disease Hospital in Yaba where the Coronavirus index patient is being managed. [Twitter/@jidesanwoolu]](https://image.api.sportal365.com/process/smp-images-production/pulse.ng/16082024/377b73a6-190e-4c77-b687-ca4cb1ee7489?operations=autocrop(236:157))

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)